Although the United Kingdom’s (“UK”) electrical vehicle ownership is growing, its transport network remains predominantly fuelled by petrol and diesel. The UK’s refineries produce less than half of the UK’s diesel requirements, with the remainder imported from various countries including, (and historically), Russia. However, the implementation of sanctions on Russian exports means the UK, and indeed much of Europe, are seeking alternative supplies of diesel. The following Martello View considers some of the challenges and opportunities this presents.

Introduction

The UK imports over half its diesel requirement and whilst the appeal of the diesel passenger car has waned recently, the demand for diesel fuel remains strong due to its key market of freight. The UK’s diesel demand has grown steadily over recent years and has rebounded faster since the pandemic than petrol, this has been supported by the post pandemic resurgence of business activity and commercial journeys (which drives diesel demand) versus a slower recovery in commuting and leisure (which drives petrol demand). The economic slowdown may temper demand growth but the need for imports will endure for some time.

The Impact of Sanctions on Diesel Supplies

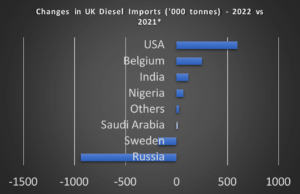

Following the invasion of Ukraine both the UK and European Union (“EU”) have implemented sanctions on Russian diesel imports which, in 2021, had supplied more than one third of imports. By the end of 2022, Russian imports were at zero, with the UK having increased diesel supplies from suppliers such as the United States of America and Belgium (as shown in the graphic below).

*Note: The data compares September – November 2021, against the same period for 2022

However, Russian diesel likely continues to enter the UK’s markets via Europe. The UK reduced its Russian imports to zero from July 2022 onwards while the EU’s ban only took effect in February 2023, until which there was significant stockpiling of Russian diesel. The UK takes significant volumes of diesel from the Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Antwerp (“ARA”) trading hub and these imports have likely been commingled with Russian fuel. Hence direct imports of Russian diesel have ceased but have indirect imports also ceased?

The advent of the EU ban will further increase competition for the finite supplies of non-Russian diesel. Some industry experts doubt that Europe will manage to eliminate Russian diesel supplies entirely, as traders and shipping companies will keep Russian fuel entering the EU, and the UK, just via more complex, roundabout routes.

The competition for non-Russian supplies creates clear economic incentives to trade Russian cargos. Countries without embargoes, or traders willing to take them, could make more than US $1 million on a standard cargo of Russian diesel versus non-Russian fuel. There are reports of Russia trading with brokers in neighbouring friendly countries, (for example Georgia), thus potentially finding other routes into the EU and UK’s supply mix. Rerouting diesel fuel trade flows through non-EU countries provides another back door into Europe for Russian supplies and this may cushion the impact of the ban and avoid any big supply crisis. However, diesel fuel prices will likely remain high due to inefficient supply routes and the numerous intermediaries in the supply chain each taking a profit margin.

Potential Impacts on Quality

The turmoil due to consumers seeking alternative diesel supplies also means that supply chains are much less transparent than in the past. In turn, this could potentially compromise the quality of diesel imports. There is currently no evidence of quality issues, but there is obviously an increased risk of sub-standard diesel fuel entering supply chains as supply pressures increase. For example, properties such as cloud point and distillation range are important as these indicate how the fuel will perform in cold temperatures (it is important to avoid solidified waxes which can clog filters and negatively impact engine performance at low temperatures). Some problematic fuels can meet the European EN 590 diesel fuel standard but still have poor winter operability and lead to vehicle breakdowns. There is a concern that such fuels which are not fit for purpose will find their way into the EU and UK’s supply chains.

This has created worry among the major fuel retailers, and some are carrying out monitoring programs and spot checks to ensure that diesel fuel quality is not being compromised. The AA reported a sharp increase in diesel vehicle breakdowns in December 2022. This increases concern that diesel fuel quality may be deteriorating, as a result of the opaque supply chains.

An Opportunity for Biofuels?

With limited import options available can Europe produce more diesel? Europe has long been short on diesel and the production of diesel from its refineries (which are generally more geared towards petrol production) is already maximised. However traditional crude oil refineries are not the only source of diesel supplies.

Biofuels are generated from biological material with renewable sources of carbon. They are drop-in liquid fuels that are functionally equivalent to petroleum fuels, and when blended with refined petrol and diesel, are fully compatible with the existing infrastructure. Biofuels potentially provide not only additional security of supply but environmental benefits.

Biodiesel is made in a process called transesterification with the end product known as FAME (fatty acid methyl ester). The feedstock is: biomass (oily plants and seeds), waste animal fat and used cooking oil. In practice, whilst legislation allows up to 7% of diesel to be FAME, the average levels are about 4%. Thus, if more biodiesel can be produced it can be blended into refined diesel without exceeding the EU’s fuel specifications.

The Russian diesel embargo and higher diesel prices would normally be expected to jump start a race to build new FAME production plants, but the reality is different. Biofuel demand dipped during the pandemic by almost 10% and has been slow to recover. Demand is also muted by higher FAME and bioethanol prices. Perhaps the greatest hurdle though is the “food vs fuel” argument, which has long been present but has been intensified by the disruption to crop production in Ukraine. This can probably only be fully solved by ensuring biofuels are based on waste food products (e.g., used cooking oil) or perhaps on later generation technology like the production of biofuels from algae.

Conclusions/Impact for the Legal Sector

Whilst the UK has excluded directly sourced Russian diesel from its supply at present, the February 2023 EU embargos on the trading of Russian diesel supplies will now make non- Russian diesel supplies even more sought after. We may see Russian diesel supplies continue to make their way into the European mix but via more circuitous routes (e.g., being routed through non-EU countries) or other efforts to disguise their source (e.g., ship to ship transfers). This will obscure supply routes and lead to uncertainty regarding supply sources and, potentially, claims relating to a breach of sanctions.

However, it is not only the source of imports that may become opaque but, also, the quality of them. Thus, it is probable we will see an increased number of issues relating to product quality and the ensuing potential for litigation.

On the non-contentious side, we could see renewed interest in biofuels, especially those that do not use a viable foodstuff as their feedstock. Participation in and funding of such projects could be useful for ESG metrics.